Night Owls and Aging Hearts: How Late Bedtimes May Raise Cardiovascular Risk

Introduction

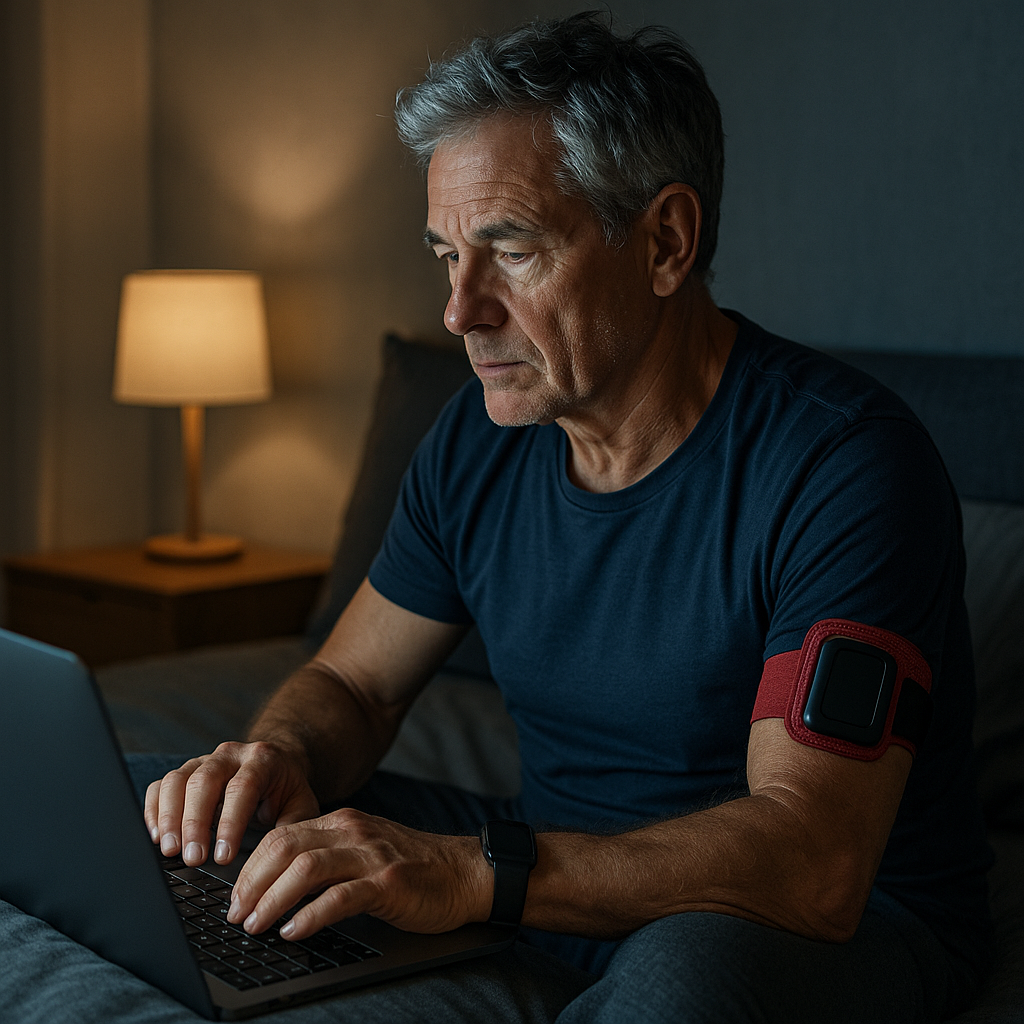

If you naturally stay up late and hit your stride after sunset, recent research suggests this habit may carry a hidden cost for your heart as you get older. A large study of more than 300,000 adults found that people who identify as “evening types”—commonly called night owls—had poorer overall cardiovascular health and a higher risk of heart attack and stroke in middle and later life compared with people who were active earlier in the day. The increased risk appeared to be stronger in women and was largely tied to common lifestyle patterns among evening types, such as shorter or disrupted sleep and higher rates of smoking.

Quick Summary

- Large observational study links natural late sleep timing with higher risk of heart attack and stroke in middle-aged and older adults.

- Many of the differences are explained by lifestyle factors common in evening types: shorter sleep, smoking, late eating, and less regular routines.

- Biological mechanisms may involve circadian misalignment, inflammation, blood-pressure dysregulation, and metabolic stress.

- Shifting habits—consistent sleep, better sleep quantity/quality, light exposure, and exercise—can reduce some risks; consult your clinician for personalized advice.

What the study found and what it means

The study followed a large cohort and compared self-identified morning people and evening people over many years. Evening-type participants had higher rates of cardiovascular events (heart attack, stroke) and generally worse cardiovascular profiles. Importantly, much of this association was accounted for by modifiable behaviors—smoking, shorter or irregular sleep, late-night eating, and lower levels of regular physical activity—rather than bedtime alone.

This was an observational study, so it cannot prove that late bedtimes directly cause heart disease. However, the findings strengthen the idea that the timing of sleep interacts with lifestyle and biology in ways that can affect cardiovascular health over decades.

Why late bedtimes may increase heart risk

Circadian misalignment

Our cardiovascular system follows circadian rhythms: blood pressure, heart rate, hormone release, and metabolic processes shift across the day. Staying awake and active late at night can misalign behaviors (eating, exercise, wakefulness) with those internal rhythms, which may increase stress on the heart and blood vessels over time.

Sleep quantity and quality

Evening types often sleep fewer hours or have fragmented sleep because social and work schedules force early wake times. Chronic short sleep and poor sleep quality are linked to higher blood pressure, impaired glucose regulation, and systemic inflammation—known risk factors for heart disease.

Lifestyle and behavioral factors

Night owls are more likely to smoke, drink alcohol later, eat late-night meals, and have variable routines. These behaviors independently raise cardiovascular risk. Conversely, morning types often have more regular meal and exercise schedules, which support metabolic health.

Sex differences

The study noted a stronger association in women. Hormonal differences, social role pressures (which can affect sleep and stress), and sex-specific responses to circadian disruption may contribute. Because hormonal transitions such as menopause influence cardiovascular risk and brain health, women may be particularly sensitive to timing-related effects as they age. For more on menopause and brain health, see this review on menopause-related grey matter changes: Menopause and brain health.

Biological pathways to watch

- Blood pressure variability and higher nocturnal blood pressure.

- Elevated inflammatory markers linked to disrupted sleep timing.

- Insulin resistance and unfavorable lipid profiles from late-night eating and short sleep.

- Reduced opportunities for daytime physical activity; lower cardiorespiratory fitness. Improving aerobic fitness can change risk—see practical guidance on VO2 max and how to raise it: Why VO2 max fell and how to raise it.

Practical steps to protect your heart without forcing a total personality change

If you’re a natural night owl, you don’t have to become an early bird overnight. Focus on choices that reduce risk while respecting your chronotype.

Key strategies

- Prioritize sleep duration and regularity: aim for consistent sleep and wake times across the week, even if your schedule is shifted later than average.

- Increase daytime and early-evening light exposure to strengthen circadian signals—get bright morning light when possible; limit bright screens and blue light in the hour before bed.

- Avoid heavy meals, alcohol, and nicotine close to bedtime; late eating can disrupt metabolism.

- Schedule regular physical activity earlier in the day when possible; exercise improves metabolic health and sleep quality.

- Address sleep disorders: if you snore, have daytime sleepiness, or wake gasping, consult a clinician—untreated sleep apnea raises cardiovascular risk.

- Quit smoking and limit alcohol—two strong, modifiable contributors to cardiovascular disease.

- Get routine medical checks: monitor blood pressure, lipids, blood sugar, and discuss heart health with your provider.

Checklist: Heart-smart habits for night owls

- Sleep 7–9 hours most nights and keep bed/wake times consistent

- Dim lights and avoid screens 60–90 minutes before bed

- No heavy meals 2–3 hours before sleep

- Limit or time alcohol and nicotine away from bedtime

- Incorporate 150+ minutes/week of moderate activity or 75+ minutes of vigorous exercise

- Schedule annual checks for blood pressure, cholesterol, and glucose

- Seek evaluation for loud snoring, pauses in breathing, or excessive daytime sleepiness

Common Mistakes

- Trying to flip your schedule abruptly: sudden large changes in sleep timing often fail and worsen sleep debt—shift gradually (15–30 minutes earlier every few days).

- Relying on caffeine late in the day: this reinforces late alertness and fragments sleep.

- Assuming bedtime is the only factor: sleep duration, sleep quality, meal timing, activity, and smoking are equally important.

- Using screens without blue-light mitigation: night-time screen use can suppress melatonin and delay sleep onset.

- Ignoring symptoms of sleep disorders: untreated sleep apnea or persistent insomnia are medical issues that merit professional evaluation.

Conclusion

Being a night owl is linked with higher cardiovascular risk in middle and older age, but the relationship is driven largely by modifiable lifestyle factors and sleep patterns. You don’t necessarily need to force an early-morning life to reduce risk—prioritize sufficient, regular sleep; reduce late-night smoking, drinking, and heavy meals; increase daylight exposure and daytime activity; and get routine medical screening. If you have cardiovascular concerns or suspect a sleep disorder, consult your clinician for tailored assessment and care.

FAQ

1. Is being a night owl genetic, or can it be changed?

Both genetics and environment influence chronotype. Some people have a strong biological tendency to be awake later, but you can shift timing gradually through light exposure, sleep scheduling, and behavioral changes. Permanent, large shifts are harder and may not be necessary if you optimize sleep duration and health behaviors.

2. If I shift my bedtime earlier, will my heart risk fall immediately?

Risk reduction is gradual. Improving sleep regularity and habits can lower risk factors (blood pressure, glucose, inflammation) over weeks to months, but long-term cardiovascular risk reflects many years of behavior and biology. Use sleep and lifestyle changes as part of a longer-term plan and coordinate with your healthcare provider.

3. How important is total sleep duration versus bedtime timing?

Both matter. Short sleep duration independently increases cardiovascular risk, while late timing can worsen metabolic and blood-pressure regulation. If you must wake early, prioritize total sleep hours; conversely, being late but getting consistent, adequate sleep is better than chronic short sleep.

4. Why did the study find a stronger effect in women?

The reasons are complex and likely involve hormonal differences, menopause-related changes, and sex-specific behavioral patterns. Women may also experience different social or caregiving demands that affect sleep. More research is needed. For related reading on menopause and brain health, see this overview: Menopause and brain health.

5. What medical tests should I consider if I’m worried?

Start with basic cardiovascular screening: blood pressure, fasting lipids, and blood glucose or A1c. If you have symptoms of a sleep disorder—loud snoring, witnessed apneas, or excessive daytime sleepiness—ask about a sleep evaluation. Always discuss concerns with your primary care clinician to determine appropriate testing.

Post Comment